To hinder or not to hinder, that is the question, warns Lance Rütimann, as he flags up concerns over the Construction Products Regulation

STANDARDS FOR products and services are at the heart of the success of the fire safety industry. Euralarm members need a fast and flexible system for setting standards, because not only is it the best way to serve the interests of customers, the industry and society, but it is also a basic requirement for a safe and secure society. Our standardisation system helps us to continue to deliver the highest levels of safety and security to citizens.

That said, according to our members, in the context of the competitiveness of the electronic fire safety industry, the impact of the Construction Products Regulation (CPR) on standardisation has unfortunately not met expectations. This industry along with many others depends on standardised product performance requirements and standardised behaviour, which is at odds with the interpretation of the CPR following the European Court of Justice judgment (CJEU) on the James Elliot case (explained further on).

For example, alarm buttons to activate a fire alarm system across Europe and the world are always red in colour. Under the CPR, this is not seen as an essential criterion and could now change with national solutions. These could lead to building occupants being confused if in one country the button is red, yet another colour elsewhere.

Our expectation of the CPR was that it would help to ensure the European wide acceptance of test laboratory results, which in turn supports the movement of construction products across Europe. But now it has taken a different turn since the CJEU judgment. Further, trying to cover a very wide assortment of products – from aggregate to electronic systems – is proving to have a negative effect on the standardisation of fire detection and alarm products.

CPR background

The free movement of goods is one of the success stories of the European project. It has helped to build the internal market from which European citizens and businesses are benefiting, and which is at the heart of European Union (EU) policies. It was that same free movement of goods that was behind the introduction of the CPR in 2011. With this regulation, the EU wanted to establish a common ‘playing field’ for products for the construction industry.

Harmonised standards

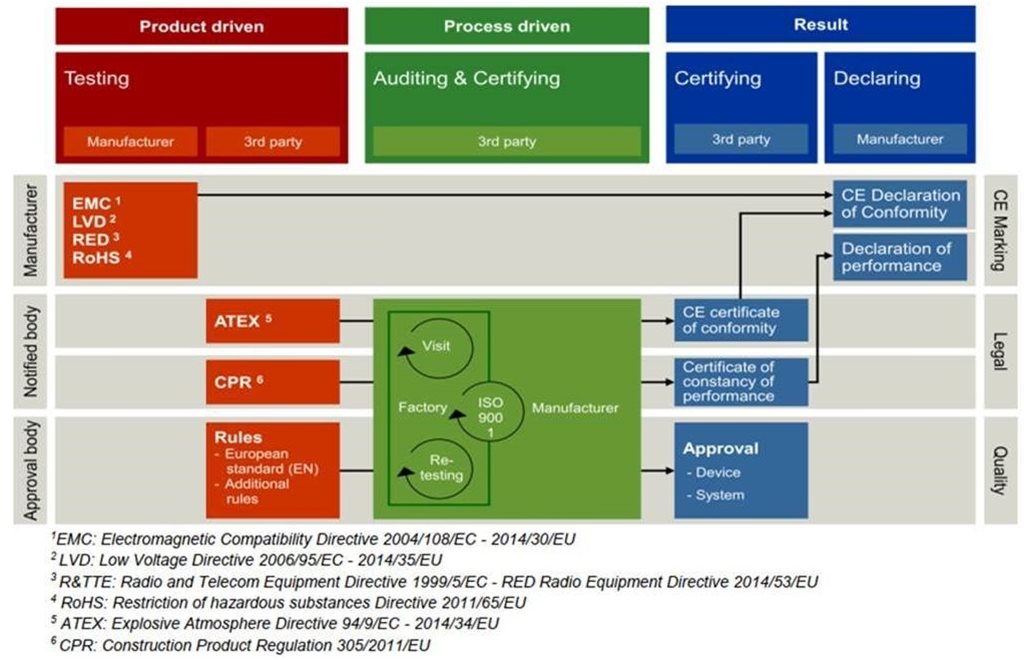

In order to assess or declare the product conformity, use is made of the so called harmonised standards. These are European standards that have been developed by a recognised European standards organisation (ESO) such as CEN, CENELEC or ETSI. They define the common technical language to be used: by manufacturers to express the technical performance of their products; by regulators to express their requirements; and by designers, contractors and other construction stakeholders to efficiently exchange information.

Providing a solid technical basis for testing the performance of products, the standards allow manufacturers to prepare a declaration of performance (DoP) for their products as defined in the CPR and to affix the CE mark. The CE marking signifies that a product complies with relevant safety, health or environmental regulations across the European Economic Area (EEA).

Working with European harmonised standards offers many benefits. Firstly, the technical relevance is guaranteed, since the standards are the result of open and transparent discussions between interested stakeholders in the ESOs. Following these discussions, a standard is adopted by one of the ESOs, which makes the European standard relevant to the market as well.

Since the European standard is requested by the EU and cited in the Official Journal of the EU (OJEU), the harmonised standards also relate to EU politics. When using a harmonised standard, it is assumed that the product complies with the basic requirements of the directive. This ‘presumption of conformity’ fulfils the circle that is needed for the free circulation of a product in the EU single market.

(Figure 1 (below): Overview of steps that need to be taken and fulfilled until the CE mark can be applied.)

One size fits all?

Overlooking the construction industry is a very wide range of building products that fall under the scope of the CPR, ranging from low tech products such as asphalt for road construction through to high tech products such as fire detection devices for buildings. Most of these products fall into categories that allow manufacturers to self declare compliance with standards.

In case they cannot declare it themselves, there are several third party testing institutes that can help. However, fire protection systems and equipment (and also, to an extent, security products) must be third party assessed and certificated before being placed on the market.

Until recently, it had looked as if working with harmonised standards for assessing or declaring product conformity was functioning well. That changed with the so called James Elliot case. James Elliot Constructions started a case at the CJEU against Irish Asphalt. The building company claimed that the aggregate provided by the asphalt manufacturer was not compliant with the specifications of the relevant harmonised standard for aggregates.

Privately produced technical harmonised standards were regarded by the CJEU as a provision of EU law. In its ruling, the Court not only addressed this specific context, but also raised the need to address some specific aspects of the functioning of the European standardisation system.

Market and standardisation

The James Elliot case triggered the European Commission (EC) to set up additional assessment processes by which harmonised standards, once elaborated, can be reviewed in retrospect. This development has brought the review and publication of standards in the OJEU to a standstill. In 2019, not one single standard was cited in the OJEU and there is no hope of change.

While the additional assessment processes for harmonised standards may not be of great importance for low tech products that remain the same for decades, they are for high tech products such as fire safety equipment. The rapid technological developments of these and other high tech products require up to date versions of harmonised standards.

What is more, product innovation using new technology is an important capability for the fire safety and security industry, in order to improve performance and usability. Most fire protection systems and equipment also employ electronics, and software that needs to be updated on a regular basis. These aspects demand that related standards and regulations are sufficiently flexible and responsive to encompass such changes. The current CPR practice clearly does not accommodate these needs.

Evaluating the situation

Quite recently, the EC evaluated the CPR to assess how much it has met its objectives and helped reduce obstacles to the internal market for construction products. Among the main shortcomings identified by this evaluation are the insufficient performance and output quality of the standardisation system, and the low uptake of simplification provisions. These factors have reportedly resulted in a lack of legal clarity, according to the EC.

Euralarm shares its conclusion that a revision and a simplification of the CPR is needed. However, it is not the production of technical standards that lead to insufficient performance and output quality, but the requirements set up by the EC for the harmonisation of standards under the CPR. From a technical standpoint, all European standards impacting the fire safety sector have been updated, but only two revised standards in the EN 54 series have been accepted by the EC, and hence cited.

Notwithstanding the disproportionate standards development cost for the industry, the changes in the CPR have created serious obstacles in exporting fire safety products outside of Europe and more generally in the competitiveness of the European industry. While our international competitors have been able to update their standards to the latest technological developments, the European fire safety industry is unable to compete because the publication of new standards is blocked.

Instead of blocking the publication of new or revised standards, the focus should be on the availability of up to date versions of harmonised standards – with shorter times between reviewing, updating and publishing. This will give the fire safety industry – as well as many other industries that depend on (advanced) technical products – more flexibility when developing standards to ensure the safety of European citizens and to preserve its competitiveness in the international market

Lance Rütimann is vice president of Euralarm, and director of industry affairs at Siemens Smart Infrastructure