Iain Cox examines regulations and guidance, explaining why compliance with regulations does not necessarily achieve resilience to fire

GIVEN THAT a building constructed to meet regulations can still burn down, the obvious question is: why is this building classed a regulatory success? On 20 June 2020, more than 100 firefighters tackled a large night time blaze at a Budgens supermarket in Holt, Norfolk. The fire and rescue service (FRS) prevented the fire from spreading to other buildings, but sadly the supermarket was beyond repair and will now have to be rebuilt.

That business had served the community for 35 years and was home to the town’s only post office. It was also doing hundreds of deliveries to people who were self isolating during the COVID-19 lockdown. For Budgens, it caused a loss of earnings along with business disruption, as the store will have to be rebuilt, while the erection of a temporary store and redeployment of staff were required in the meantime.

In contrast, a bakery oven fire in December 2018 at a Sainsbury’s store in Altrincham, Cheshire, had a very different outcome, as an automatic sprinkler system activated and extinguished the fire before the FRS arrived. The store reopened three hours after the fire started, with damage costs limited to less than £500. That is a minuscule figure compared to the substantial cost of rebuilding the Budgens supermarket, the loss of business incurred and the impact on the local community.

Building regulations

Under current building regulations guidance, the Budgens supermarket was below 2,000m2 in size, and so was not guided to install sprinklers. Should there not be flexibility in the system to ensure that ‘critical’ buildings such as these can also be effectively protected from fire?

Whether achieved through a greater ability to emphasise the critical nature of a property through local powers or an improved national regime, we need to ensure that large and ‘critical’ buildings are protected. The Holt Budgens site is a good example of a building the community can ill afford to lose, but equally losing a school, medical centre, hospital or sports centre would have a significant impact.

Compared to sprinkler requirements for similar buildings in other European countries, where on average sprinklers are required in industrial and commercial buildings of 3,000m2 in size, the fire safety building regulations guidance in this country for industrial and commercial buildings is very relaxed because the remit of the building regulations relating to fire safety is limited to ensuring the safety of occupants in the event of a fire.

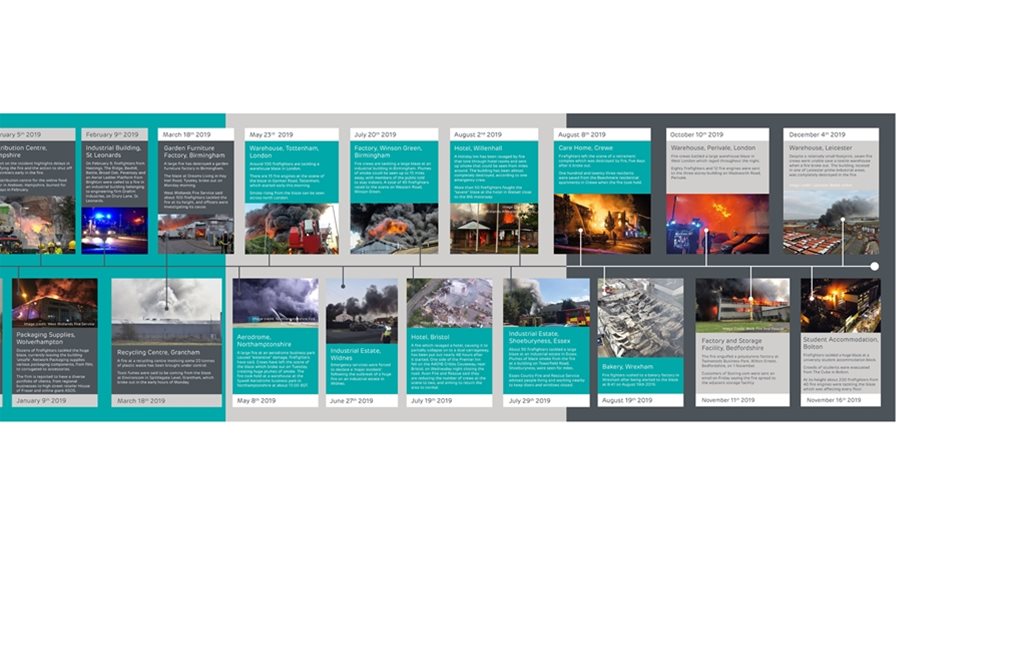

From that perspective, the regulations here are effective: there are very few deaths or injuries as a consequence of fires in industrial and commercial buildings. The outcome of the fire is a ‘success’ if all occupants evacuate safely, even if the building is badly damaged or destroyed. However, the regulations do not take into consideration the protection of property – such as a building’s ability to withstand a fire – which is a primary reason for the fact that we record 11 fires every month in England that badly damage industrial and commercial buildings.

The problem in making buildings easier to get out of and changing how we construct them is that this has made them, in effect, more vulnerable to fire. The building will survive for the period it takes to get people out, after which we transition into a period where the inherent resilience diminishes. There is a twisted logic that says the building is disposable in the event of fire.

Sustainability questions

One would also question the sustainability of such an approach, given our increased attention on conserving energy and resources to transition to a greener economy. Regulations and green rating systems may well recognise a high performance building, but you only have to look at the devastating consequences of a fire to realise that a building’s sustainability does not account for its immunity to fire.

This was the case in 2018, when a fire completely destroyed a newly opened Gardman garden products distribution warehouse in Daventry, Northamptonshire. The building achieved a ‘very good’ BREEAM rating for its energy efficiency. Sadly, this was not matched in terms of resilience, as the building lacked active protection such as from sprinklers. The fire had far reaching consequences, with rebuild costs of £30m and the eventual sale of the Gardman garden supplies business.

When we measure the performance of a building, we should be measuring the performance across the board. Sustainability is one very important element, but sustainability must include durability. Discussion often takes place about sustainability, but not about interruptions such as damage to a building caused by floods, storms or fire. A building’s sustainability or green rating is focused on energy performance, but those environmental credits are instantly lost when a building burns to the ground. Future views on conserving resources should also look at the building materials themselves and how they are used over time. To be truly sustainable, buildings should be resilient to fire, and sprinkler systems are proven to be the most effective means of fire protection.

Business continuity

There is much to be said about business continuity in the event of a major disruption such as a fire, but this needs to be part of a wider risk management strategy. Judging by the many fires across the commercial sector, there is a disconnect between the need for business continuity planning and the outcome from regulations.

If one of the big risks is that you might significantly damage a factory critical to your whole operation and you rely on regulations, there is a large gap. That continuity plan will need to go further – you will have to find new premises, machinery and logistics in order to recover. A more successful strategy would be to protect the very critical elements of its operation which are vulnerable in the first place. It is clear that resilience has been sacrificed for a particular goal of compliance with regulations, but unfortunately key stakeholders cannot see it.

Samuel Garside House

The misunderstood nature of the regulations is also evident when you look at fire in a residential development. A review into a fire that engulfed Samuel Garside House, a six storey block of flats in Barking, east London, in June 2019 found that the fire was fuelled by the building’s external timber balconies, even though they complied with regulations at the time.

Thankfully, there were no fatalities, but the fire had a huge impact on the residents. Eight flats had to be rebuilt and a further 39 could not be occupied until repairs were completed. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, many residents found themselves homeless. We expect that buildings will be safe, but beyond that I am not sure we set such demands on buildings in terms of their performance in the face of fires and floods.

That is often assumed as a basic need and not an expression of interest. We think we have this now, but recent evidence shows the unintended consequences are that some buildings have fire safety challenges. The building owners are facing remediation works to buildings that will address fire safety but will not make the building more resilient – they are to meet the minimum outcomes required by regulation.

In light of Grenfell, the industry is talking about raising the bar of standards and competence to meet current needs in terms of fire safety. Perhaps we should be raising the bar to ask: what is the outcome we wish to see? The only way to do this is to think hard about the outcome we see in fire. If we do not try to change the outcome, regulatory success will continue to look like the examples we have seen

Iain Cox is chair of the Business Sprinkler Alliance